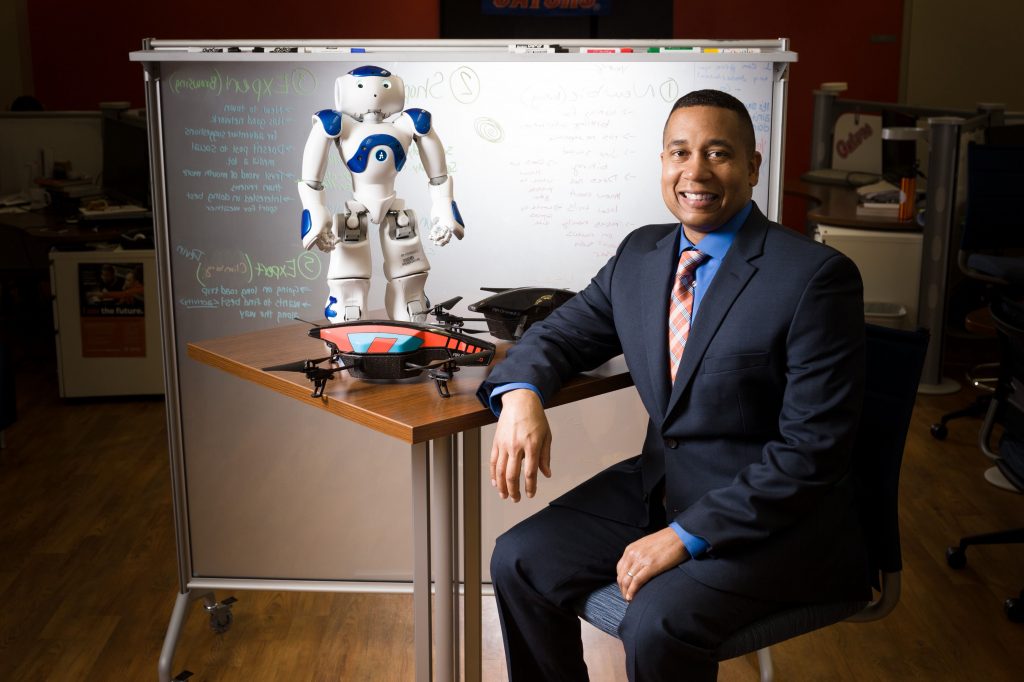

Juan E. Gilbert, Ph.D., created the Prime III software voting system as a model for how to make elections more secure — and more inclusive.

During this unprecedented election season, there has been a focus on safety and security for voters and voting systems — but equally paramount should be the issue of accessibility.

That belief drove Dr. Juan Gilbert, an award-winning computer scientist and diversity advocate of the University of Florida, to invent the Prime III voting software system. It provides different operation modes for the same, universal device to accommodate all voters regardless of mobility, vision, hearing or other impairments.

“If you have one machine that everyone could use independent of their ability or disability,” says Gilbert, “you get not only more equity, but also a more secure environment” by avoiding use of separate voting technologies that could be vulnerable to tampering.

With funding from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission and the National Science Foundation, Gilbert developed and tested the system over the past decade, and then made it open source. His technology has already been used in state, federal and local elections, including the 2020 election cycle.

Today Gilbert is testing an innovative new design of his system that combines digital and paper voting methods. He’s also leading a research group dedicated to defining and developing more equitable artificial intelligence.

We spoke with him about his work, the effects of social and racial injustice and the importance of inspiring others in the context of invention.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What problems or questions drew you to the realm of voting?

After the 2000 presidential election there was a lot of concern about the integrity of our elections. In 2002, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act to provide accessible voting equipment for people with disabilities, but I felt we needed more than that. We needed one way for everyone to vote or one technology. That’s what prompted me to get involved.

What was your solution?

What was your solution?

I created Prime III, the first open-source, universal design voting system. First generation voting was paper. Second generation used DREs, or Direct Recording Equipment, where you vote and it stores your vote on a removable drive for later tallying. So Prime III is third generation, a ballot marking device with a universal design.

Why is universal design crucial to making voting more equitable?

Universal design is the principle of designing something to accommodate the largest number of people possible. In the context of voting, when the Help America Vote Act was passed, it had a provision that said every voting precinct had to have at least one accessible voting machine for people with disabilities. From my perspective, that created a separate-but-equal connotation. That has never worked well. But if you have one technology that everyone could use independent of their ability or disability, you get not only more equity, but also a more secure environment. Essentially, if more people use the technology, the higher chance you have of detecting errors or hacks. If everyone votes on the same machine in the same precinct, you have greater accessibility and security.

How many people have used your technology to date?

It’s the only open-source voting system that’s ever been used in state, federal or local elections in the United States. It was adopted for statewide use in New Hampshire and is being used as the remote accessible voting option for people with disabilities in Butler County, Ohio. The nation’s largest voting machine manufacturer has created a machine modeled after what we’ve done. So as far as people voting on technology inspired by our work, I would say millions.

You’ve testified before Congress about the importance of open source software. Why?

If software is open source, you can look under the hood and see exactly how it works. If it’s private, there could be allegations of mischief and no one would be able to verify or discredit them with certainty. That’s the difference, and it is significant when we’re talking about elections.

What are the differences between designing software versus hardware?

When I first designed Prime III, it was designed to be independent of hardware. It’s still somewhat that way, but now we have a (patent pending) new design for a hardware system that we’ll be testing soon. Imagine a piece of glass that’s like a touch screen where you can make a selection, and then they print right behind the glass. You see exactly what’s printing right in front of you. The idea is that we’re basically turning paper into a touch screen.

When do you hope to have the new technology rolled out?

We have a prototype that was just delivered. I’m hoping to do some studies in early spring and have some results before the summer to really show that this technique will be the most secure method of voting ever.

You’ve said that algorithms and computing will be the next frontier for addressing racial inequities. How can technology contribute to racial injustice, and how can it help solve it?

I think people understand bias in AI is a reality. You see it in predictive policing and other algorithms. The question is, how do you address it? Here at the University of Florida, I’m leading a group in equitable AI. From my perspective, equitable AI has two aspects: number one, an AI system who has a primary goal of creating equity is an equitable AI system. To date, I’ve only found one, and it’s funny because I’m the one who created it. It’s a tool called Applications Quest that deals with affirmative action, diversity in hiring and admissions. So that’s an equitable AI. The other classification would be AI whose primary goal is not to create equity, but outcomes, decisions or recommendations that are equitable. We’re doing research on how to judge systems and evaluate them along these metrics and determine if they’re equitable.

What challenges have you faced on your path to invention and entrepreneurship?

Learning about inventing — the patent process and all of those things — was something I didn’t receive much education on. Over time, I learned and that has worked out, but that was a big hurdle. That, and getting technology transferred into the real world. That’s more challenging than most people realize. It’s a huge task that requires full-time attention.

Did you have mentors along the way?

Did you have mentors along the way?

I had mentors through my career, but with respect to invention, I was pretty much on my own. That said, my parents were an inspiration. My dad only had an eighth-grade education and he fought in the Korean War. He came back and ended up having his own paint and body shop business. Engineering-wise, I learned a lot in his shop. My mother graduated from high school and she worked in the school system. She was an aide for hearing-impaired kids. I didn’t realize it at the time, but her work definitely had an impact on me.

What advice do you have for other would-be inventors?

Number one would be you have to be passionate about your idea. Number two, understand that this is a marathon, not a sprint. The concept of overnight success doesn’t exist. You’ve got to persevere.

You were the only Black computer science PhD candidate in your cohort. Now issues of diversity, equity and inclusion are coming to the forefront in academia and STEM. How do you help inspire the people coming up behind you?

Because I didn’t see someone like me growing up, it never occurred that I could do the things I do. I didn’t have any role models. For me now, it’s about telling my story. That’s why I think it’s important to communicate with young people. That’s why I’ll speak to kids at schools. It’s about working with my students and helping educate and expose them and others to these opportunities. A lot of times, they don’t even know these things are available to them. My research lab is very diverse. It is predominantly female, predominantly African-American and has been for years. It’s part of who we are. It’s part of what we do.

This article was originally published on Invention Notebook by The Lemelson Foundation.