CIS 6930 Cryptographic Protocols

Analysis of Authentication Protocols

Notes on Presentation - 30th Sep, 2003

Giridharan

Sugabrahmam (gsugabra@cise.ufl.edu)

Outline

of the Topic - http://www.cise.ufl.edu/~gsugabra/outline.doc

(Size: ~ 2 MB)

![]()

- Introduction

Authentication merely ensures that the individual is

who he or she claims to be. If every

device communicating on behalf of a person or other entity shared a secret key

with every other such device, and these keys were never compromised, canceled,

unsubscribed, or otherwise expired, then basic authentication protocols might

be unnecessary. But this wont be the case. So we require an authentication

protocol that can establish a key for a secure communication session. An

authentication protocol is an exchange of messages having a specific form for

authentication of principals using cryptographic algorithms.

The Needham and Schroeder authentication protocol revolutionized security in distributed systems. An Adaptation of this protocol - Kerberos has become universal. However, it was not long before a flaw was found in this protocol. Needham and Schroeder then published a revised version of their protocol.

The existence of a subtle flaw in a previously trusted protocol stressed the need for formal methods for analyzing authentication protocols. In fact, many authors [BAN, GNY et all] praise the merits of their analysis techniques with their ability to discover the flaw in the Needham and Schroeder protocol.

2. Approaches to the Analysis

- Type I - Verification Tools

Ø Model and verify protocols using specification languages and verification tools not specially developed for the analysis of such protocols.

Ø The idea is to treat a cryptographic protocol as any other program and attempt to prove its correctness

Ø One of the tools: LOTOS for Protocol Specification models

Ø Problem: No concrete results have been reported using this method.

Ø Use of Finite State Machines for analysis - they do not guarantee security from an active intruder.

This type was able to prove the correctness of the protocol alone, however it failed to prove the security of the protocols.

- Type II - Expert Systems

Ø Protocol designers develop and investigate different scenarios.

Ø Begin with an undesirable state and attempt to discover if this state is reachable from an initial state

Ø Identifies flaws better than Type I approach but still security is not guaranteed.

Ø Useful for analyzing known weaknesses in protocols, and generating message lists to exploit those weaknesses.

- Type III - Algebraic Term-rewriting properties

Ø Based on the algebraic term-rewriting properties of cryptographic systems. -- Introduced by Dolev and Yao

Ø Considers Authentication protocol as exchange of words.

Ø Define

Algebraic operations on these words, such as encryption and decryption.

Ø More

recent applications have provided automated support for the analysis, and have

enabled a user to query the system for known attacks.

Ø The Type III approach generally involves an

analysis of the attainability of certain system states. In this regard, it is

similar to Type II approach.

Ø However, the Type III approaches try to show

that an insecure state cannot be reached, whereas the Type II approaches began

with an insecure state and attempted to show that no path to that state could

have originated at an initial state.

- Type IV - Logics (Most Commonly used approach)

Ø Doxastic logic – Based on belief. The reasoning system uses rules about how belief is propagated to establish new beliefs.

Ø Epistemic logic - Based on knowledge. The reasoning is similar to reasoning in doxastic logic, but these logics are used to reason about knowledge instead of belief.

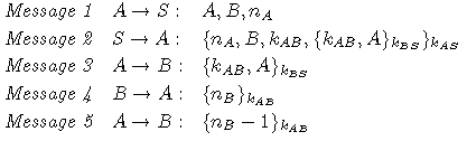

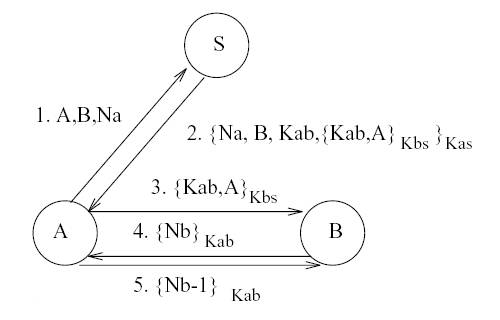

- Needham and Schroeder’s Shared key protocol – Used by many authors to check their analysis techniques.

We

represent a protocol step as A à B: Message. The Figure below shows the

Needham and Schroeder’s Shared key protocol [NSSK] authentication protocol.

- Type IV – LOGICS (in detail)

BAN Logic – Discussed by Dr. Nemo

- BAN Notation & Rules

Discussed by Dr. Nemo

- Goals of Authentication

First level beliefs:

·

A believes A ![]() B

B

·

B believes A ![]() B

B

Second level beliefs:

·

A believes B believes A ![]() B

B

·

B believes A believes A ![]() B

B

Any logic-based method to analyze an authentication protocol will try to derive these two levels of beliefs in order to state that the authentication protocol is flawless. To derive the beliefs, we make use of the Rules, assumptions and notations of a particular logic method, say BAN in this case.

The Denning - Sacco Attack on

Needham Schroeder’s protocol

[BAN Analysis of NSSK protocol available in the following link]

[ http://www.cise.ufl.edu/~gsugabra/analysis.pdf - (page number 8- Section 2.3) ]

- This Attack relies on the fact that Bob has no way to actually be assured that Message 3 is fresh.

- Attacker spends time till KBS expires and cracks the KBS key to

get the session key. Attacker can work till lifetime of KBS.

- This attack

is not directly uncovered by a BAN analysis of the protocol; When BAN logic is

used to derive the goals of authentication, some where in the middle, we will

have to make a dubious assumption that B believes fresh (![]() ). Without

making this assumption we cant proceed with the analysis of NSSK (Needham

Schroeder’s Shared key exchange protocol) using BAN. After making this

assumption we were able to derive the correctness of the NSSK protocol by

deriving the authentication goals stated above. But in fact there is a flaw in

NSSK protocol that couldn’t be discovered by BAN analysis because of the

dubious assumption.

). Without

making this assumption we cant proceed with the analysis of NSSK (Needham

Schroeder’s Shared key exchange protocol) using BAN. After making this

assumption we were able to derive the correctness of the NSSK protocol by

deriving the authentication goals stated above. But in fact there is a flaw in

NSSK protocol that couldn’t be discovered by BAN analysis because of the

dubious assumption.

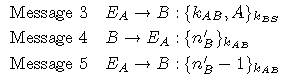

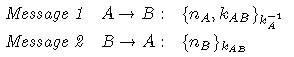

Flaw in BAN logic ~~~ as Claimed by The Nessett Protocol

(This is why BAN logic was extended)

The following is the Nessett protocol for authentication, which he used to claim that BAN logic has a flaw in it.

Nessett said that a significant flaw exists in BAN logic. He went ahead with the following steps to derive the goals of authentication.

Idealized Nessett Protocol

Annotation Premises

Initial State Assumptions

Nessett Protocol Derivations

First order

B

believes ![]()

A believes ![]()

Second order

A Believes B believes ![]()

B Believes A believes ![]()

From the Derivation of the Goals of authentication, BAN analysis proves that Nesett protocol is flawless. But in fact the message one is almost in clear text.

Message 1: {nonce of A,

Symmetric KeyAB }k-1A

Anybody can decrypt this message 1 by using the key KA (Public key of A) and get to know the symmetric key KeyAB. So this protocol in fact has a major flaw, but BAN analysis wasn’t able to detect the flaw in the protocol. This is what Nesett argued.

BAN replied back saying that Nesett had made a blunder in making the Initial state assumptions. Nesett makes an assumption that KAB is a good key for A and B alone (which is in fact a wrong assumption). BAN replied that this absurd assumption lead to absurd conclusions.

But still people felt that there is a need to detect flaws in such protocols, but they couldn’t express the protocol using the notations in BAN. This motivated many people to come up with new logics, which extended BAN by adding more notations in them.

Extensions of BAN -- GNY, AT, VO

- Built over BAN logic

- Each one Brought distinct addition

- SVO Logic --Unified the predecessors

SVO

SVO

presented a logic for analyzing cryptographic protocols which encompasses a

unification of four of its predecessors in the BAN family of logics, namely

those given in [GNY90], [AT91], [vO93], and BAN itself [BAN89]. It was also

compatible with the four logics GNY, VO, AT and BAN. It means that the

notations in any of these four logics can be represented through SVO. And SVO

had many more notations, which were not expressible by other logics. This made

SVO very powerful by combining all other logics and having its own new

notations.

The

Notations, Axioms and Rules are given in the Outline. The link to outline is

specified in the beginning of this document. The SVO Notations are

self-explanatory.

Steps

followed by SVO to analyze a protocol:

- No idealization Required

-

Mention Initial State Assumptions

-

Received Message Assumptions (Annotated protocol)

-

State Comprehension

Assumptions

-

State Interpretation

Assumptions

-

Derivations – First order & Second Order

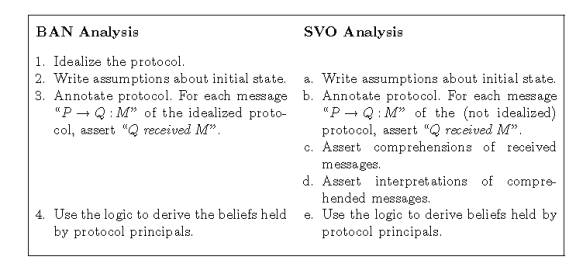

The following are the differences

between BAN Analysis and SVO analysis.

Mention Initial State

Assumptions:

Unlike BAN, we do

not idealize the protocol first. These Assumptions vary for each protocol. The

outline mentions the NSSK initial state assumptions. These assumptions are the

ones, which each principal believes before the protocol run. (Few assumptions

are common… like A and B believes that they have a key which holds good to communicate

with S. -- KAS and KBS, respectively. …. A and B believe that S controls their

symmetric key. Now we will have to derive that this key is good and whether A

and B believe that it is good – First order goal of authentication … and so

on.)

Note that P8

mentioned in Initial state assumptions of NSSK protocol (refer outline) is a

dubious assumption.

Received Message Assumptions (Annotated

protocol):

This step is the

same as the annotation assumptions in BAN, except that the specified protocol

is used, not its idealization. This means that plaintext is not eliminated and

these premises can be read directly from the specification.

If the

specification says A à S: {nonce} we convert it into something like,

S received {nonce}

Idealization:

Idealization is split into comprehension and

interpretation.

Comprehension

Assumptions:

In this step, we

express that which a principal comprehends of a received message. The move from

the received message assumptions is usually straightforward in practice.

Example:

Specified

protocol: A à S: (A, B, nA)

Annoted

protocol: S received (A, B,

nA)

Comprehension

Assumptions: S believes S

received (A, B, <nA>*s)

If you take a look

at the Comprehension Assumptions made for NSSK protocol analysis (in the

outline), it has few Asterisks symbols before S, A and B in P14-18. The

notation <X>*P means that either P doesn’t know X or doesn’t

recognize X.

Therefore in the

Comprehension Assumptions we mention an asterisk + principal’s name to denote

that the principal doesn’t know the value inside angular brackets.

Interpretation

Assumptions:

These assumptions

are essentially the replacement for idealization. In these assumptions, we have

to assert how a principal interprets a received message (as that principal

understands it).

In idealization, there is a natural and correct tendency to interpret message components using formulae expressing the intent of the sender. By placing interpretation after annotation and comprehension, the focus naturally shifts to how the intent of the sender is understood by the receiver. That is, focus shifts from the meaning the sender had intended to the meaning that the receiver attaches to a received message.

Refer to P19-P22 in outline for NSSK Interpretation assumptions.

The interpretation

premise for the first message is omitted because it will play no role in the

derivations. Mostly we stress the freshness of the key and how good the key is,

in the Interpretations assumptions. Then we combine two or more assumptions.

Derivations

for Sender and Receiver:

Once we are done

with the assumptions, we can derive the beliefs based on the axioms and rules.

The outline specifies the derivations of the goals for sender and the same

logic can be used to derive goals for receiver. But it still makes a dubious

assumption, by which SVO concludes that failed proofs sometimes reveal attacks.

If we don’t mention the dubious assumption then we cant prove this protocol. So

SVO concludes that this NSSK protocol has a flaw.

The Nessett Protocol

in SVO

The Nessett Protocol

(mentioned in page 4) claimed that BAN logic had a flaw. And BAN fought back

saying Nesett made absurd assumptions. SVO can be used and can prove that

Nesett protocol has a flaw. This is achieved by making use of the negation

notation.

Lets say E is an

eavesdropper. So we can place a requirement,

![]()

Now it is

perfectly reasonable, for every message M of this protocol to add to the

annotation assumptions that E received M. It then becomes trivial for the

Nessett protocol to derive

![]()

… which proves that

Nesett protocol has a flaw.

Links:

Outline: http://www.cise.ufl.edu/~gsugabra/outline.doc

NSSK Analysis: http://www.cise.ufl.edu/~gsugabra/analysis.pdf

[Using BAN logic:

(page number 8 - Section 2.3)]

[Using SVO logic:

(page number 20 - Section 3.4)]